What are carbohydrates and how do they affect your blood sugar?

Published

Key Article Takeaways

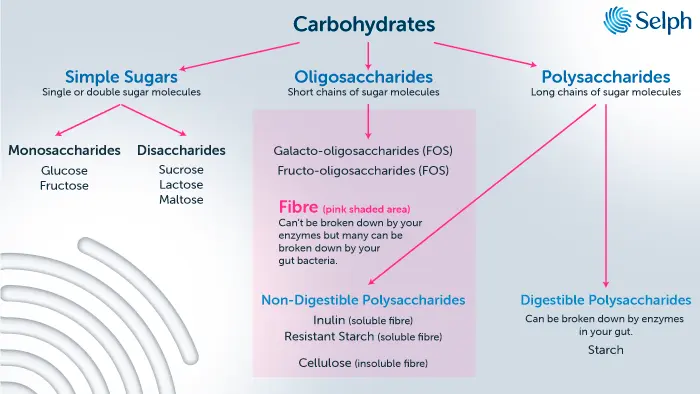

- Carbohydrates can be split up into simple sugars, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides.

- Simple sugars are mono- or- disaccharides like glucose or sucrose.

- Oligosaccharides, such as fructo-oligosaccharide, are short sugar chains which can’t be digested by your body.

- Polysaccharides are long sugar chains. Some, like starch, can be digested. Others, like inulin, can’t be digested by your body's enzymes.

- Non-digestible carbohydrate is also known as “fibre” and has many health benefits including supporting your gut microbiome.

Do you know your fructose from your fructans? Your sucrose from your sucralose? Your FOS from your GOS? Your starch from your… resistant starch?

If these terms sound vaguely familiar from your GCSE biology but you’re a little hazy on the details then you’re not alone. But if you’re serious about understanding how your body handles sugar and how it relates to your metabolic health, it’s crucial to have a basic understanding of what carbohydrate actually is and the various forms you’ll find in your food. After all, something caused that blood sugar spike…

So what are carbohydrates?

Simply put, carbohydrates are molecules containing carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, with the hydrogen and water atoms in a ratio of 2:1 - the same as water (H2O). Carbohydrates come in a couple of different arrangements: monosaccharides, disaccharides, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides.

Simple sugars

When we talk about “sugar” we’re usually referring to simple monosaccharides and disaccharides. Monosaccharides are just single sugar molecules, such as glucose, fructose and galactose. Glucose is the main sugar used by your body and is what we’re looking at when we measure blood sugar. Your brain almost exclusively uses glucose for energy and if blood glucose levels drop too low you’ll die.

Disaccharides are just two monosaccharides stuck together. For example, two glucose molecules stuck together makes maltose, whereas a molecule of glucose stuck to a molecule of fructose makes sucrose. Sucrose is the sugar that you cook with or put in your coffee.

Our small intestine is very good at absorbing these simple sugars quickly and dumping them straight into our bloodstream where they can lead to spikes in blood glucose if we’re not able to metabolise them quickly. Simple sugars are also known as simple or refined carbohydrate.

Oligosaccharides

If you join a few more sugar molecules together, say 3 to 10, you can create oligosaccharides. Oligosaccharides you might have heard of are fructo-oligosaccharide and galacto-oligosaccharide or FOS and GOS.

Our gut can’t break down these oligosaccharides so they pass from the small intestine to the colon where they’re a major energy source for our gut bacteria. For this reason, FOS and GOS are also known as prebiotics.

Polysaccharides

If you keep joining sugar molecules together you can create even long sugar chains, called polysaccharides. From a metabolic perspective, polysaccharides can be broadly divided into digestible and non-digestible.

Starch is a digestible polysaccharide made of long chains of glucose molecules - called glucans - and is used by plants to store energy. Starch is the major type of complex carbohydrate. Unlike simple sugars which can be absorbed quickly in your gut, you can’t absorb polysaccharides directly. It takes time for enzymes in your gut to break down polysaccharides into simple sugars that can be absorbed.

Inulin is a non-digestible polysaccharide and it’s made up of long chains of fructose (“fructans”). We don’t have the enzymes necessary to break down inulin in our gut so we can’t digest it. However, bacteria do possess the enzymes to break down inulin and it’s an important source of energy for our gut bacteria and is another example of a prebiotic.

Some polysaccharides can’t be digested by us or our bacteria. Cellulose is the main example. This is polysaccharide used by plants to give them structure (e.g. it’s a major part of bark). Celery is mainly composed of cellulose and you pretty much excrete it intact.

Are inulin, GOS, FOS and cellulose types of fibre or carbohydrate?

Inulin GOS, FOS and cellulose are all examples of fibre. But fibre is actually just another word for all the plant carbohydrates that we don’t have (human) enzymes to break down. This means pretty much everything in the plant is “fibre” except starch.

Fibre is actually just another word for all the plant carbohydrates that we don’t have (human) enzymes to break down.

There are two types of dietary fibre - soluble and insoluble. As the name suggests, soluble fibre dissolves in water although many form a viscous gel in the gut as they retain water. Soluble fibre is a major part of fruits and vegetables and includes inulin, oligosaccharides and “resistant starch”. Resistant starch is a type of starch that is “resistant” to digestion by our gut enzymes. It can occur naturally, in legumes for example, or when some carbohydrates are cooked and then cooled, like rice or potatoes.

In general, all of these soluble fibres pass through the small bowel and into the colon where they provide the major energy source for our microbiome through the process of fermentation. In addition to supporting the microbiome, soluble fibre helps to create a feeling of “fullness” after eating and promotes bowel motility, preventing constipation. Fibre may also act to slow or prevent the absorption of fat and simple sugars from the gut which may improve glucose control and lower cholesterol. A higher fibre consumption is also associated with a lower risk of developing bowel cancer.

Insoluble fibre is mainly cellulose and is thought to be biologically inert, meaning that it doesn’t participate in any metabolic reactions in your body. However, it’ll still help with a feeling of fullness after eating and does add bulk to the stool which can help with bowel motility.

Check out figure 1 below to see how all the different types of carbohydrate fit together.

How to understand carbohydrates on your food label

Now that you’ve got your head around what carbohydrates actually are, you should be in a much better place to understand what the information on food labels means and ultimately, what’s actually on your plate.

Generally you’ll see something like this:

| Nutritional information (per 100g) | Spaghetti | Muscovado Sugar | Chickpeas |

| Total carbohydrates | 70g | 95g | 17g |

| of which sugars | 1.2g | 95g | 0.2g |

| Fibre | 3g | 0g | 7.6g |

So “Total carbohydrate” refers to the total amount of digestible carbohydrate in the food. In the UK, it doesn’t include fibre and you’ll find fibre listed separately. This can be different in other countries where total carbohydrates include digestible and non-digestible carbohydrates.

“Of which sugars” refers to the portion of carbohydrate that is simple sugar - monosaccharides and disaccharides. You’ll remember that these are also called refined carbohydrates. So, muscovado sugar is 100% refined carbohydrate as you’d expect.

In contrast, for spaghetti, only 1.2g of the total carbohydrate is simple sugar. The rest is complex carbohydrate - which will be starch.

Food labels often don’t distinguish between soluble and insoluble fibre.

And where does “glycaemic index” fit into all this?

Glycaemic index (GI) is a measure of how quickly a food will raise your blood sugar. It’s given as a number between 1 and 100. For reference, glucose has a GI of 100. Broadly, the higher the proportion of simple sugar out of the total carbohydrate, the higher the GI. However, the other constituents of the food - fat, protein and fibre - can also affect how quickly the sugar from a food is absorbed and therefore affect the GI.

In general, we want to avoid high GI foods, such as Coca-Cola, because they cause rapid spikes in blood sugar. In contrast, low GI foods, such as whole grain pasta, are absorbed slowly and cause a gentle rise and fall in blood sugar.

What are calories?

People often equate calories with carbohydrates. However, a “calorie” is just a way of measuring energy and it’s not specific to carbohydrates. 1 kilocalorie (kcal) is defined as the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of 1kg of water by 1oC. Very practical.

Digestible carbohydrate, fat and protein represent the major sources of energy or calories in food. Fibre is only broken down by bacteria so contributes very little to the total usable (by you) energy content of food.

Not all calories are created equally! Where they come from matters.

Fat is the most energy-dense food macromolecule and contains 9kcal of energy per gram. In contrast, carbohydrate and protein both provide about 4kcal of energy per gram. Once in your body, this “energy” is either used straight away or stored as glycogen or fat. However, the food source of the energy may actually impact whether that energy is used or stored. This may contribute to weight gain. So we’re coming to realise that not all calories are equal! Where they come from matters. But this is a story for another day.

Are “sweeteners” a type of carbohydrate?

So if you check out the label on the back of a Diet Coke, you’ll see there are no carbs, no sugars and no calories. But it still tastes sweet. That’s because it contains the artificial sweetener aspartame. Aspartame tastes about 200 times sweeter than sucrose. So you need 200 times less of it to provide the same level of sweetness as sucrose. Aspartame, like many other artificial sweeteners such as sucralose and acesulfame, is not a carbohydrate. However, it does still provide about 4kcal energy per gram but because you need so little of it to provide a sweet taste, it effectively adds very little calories to food.

There are also “natural sweeteners” that occur in plants and are many times sweeter than sucrose. Stevia is a common example.

Sweeteners are generally considered safe at the levels a person would typically consume them. However, some research has associated them with negative health outcomes and it’s possible that they have effects on the gut microbiome1.

Whether you choose to consume sweeteners or not is really a matter of personal preference but just because something provides zero calories doesn’t mean it’s “healthy”. Even without the sweeteners aspartame and acesulfame, Diet Coke provides no nutritive value and contains other substances that are probably best avoided or indulged only occasionally.

What’s a low carbohydrate diet?

Although not all calories are equal in terms of how they affect your metabolism, it is still the case that to lose weight, you need to reach a caloric deficit. I.e. consume fewer calories than you burn. The three main ways to do this are caloric restriction, dietary restriction and time restriction.

The three ways to cut calories

- Caloric restriction: restricting the total number of calories consumed in a day, regardless of where they come from.

- Dietary restriction: limiting consumption of a specific food group. Usually carbohydrates or fat.

- Time restriction: limiting the time in which you allow yourself to eat.

A low carbohydrate diet is an example of dietary restriction. A carbohydrate intake of under 130g per day is often considered to be “low carb” whereas an intake of 20-50g/d is considered to be a “very low carb diet”2. A no-carb diet is also called a ketogenic diet, because if you consume no carbohydrate, your body creates ketones from fat as a source of energy to preserve glucose.

Like many diets, low carbohydrate approaches can help with weight loss and have been shown to improve sugar handling3. But losing weight is rarely the problem; it’s maintaining weight loss that's difficult. To do this you need a diet you can sustain in the long-term. Many people find this challenging with very-low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets. If you’re thinking about trying to change your diet to lose weight, the best advice is to go for something you think you can live with.

Get tips on better health

Sign up to our emails on the better way to better health.

We'll keep you up-to-date with the latest research, expert articles and new ways to get more years of better health.